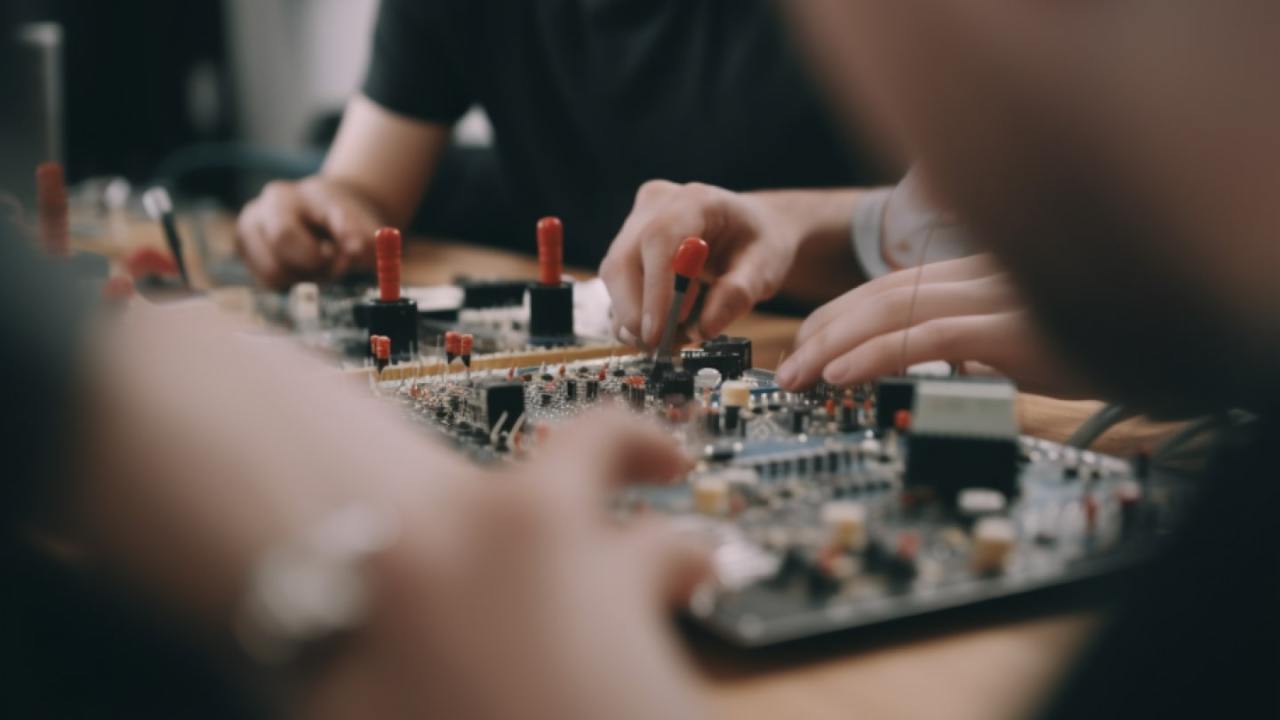

Why We Hire Makers as Leaders

My title might be “managing director,” but don’t be fooled. I’m a designer and developer at heart, just like the individuals I lead.

My maker skills come in handy when I’m in the trenches with my team. I can see failure from a mile off, sketch out wireframes at lightning speed, and jump into a codebase without hesitation. Clients love that I can roll up my sleeves and get into the action, which works to my advantage when it comes time to close a sale.

But I’d be lying if I said my background only makes my job easier. When my team is stuck on a tricky prototype, for example, I sometimes have to stop myself from stepping in. I’m fast and good at what I do (and humble, too), so I have to remind myself that seizing the reins would stunt my team’s growth.

Still, if my own experiences have taught me anything, it’s that makers make amazing leaders. That’s why we hire people who create and teach them to lead as they go.

Our ‘Makers as Leaders’ Policy

Our strategy to turn makers into leaders came to us somewhat organically. Skot Carruth, Philosophie’s CEO and co-founder, and I are both designers, so we wanted to hire more people like us. In the early days, we tried hiring a few project manager types, but they struggled to gain the respect of our clients, most of whom are also makers.

As a small firm, our policy has paid off in practical terms. Any of our leaders can jump into projects when things start going sideways or need a speed boost. Our clients appreciate that our billed rate includes directorial oversight, which means an expert engineer or designer is always available to join a project and help code.

Externally, we’ve found that our approach keeps clients engaged. One of the makers on each team doubles as an engagement lead, a role that’s responsible for the client’s satisfaction and the overall success of the project. That way, our clients never feel like they’re spending money on a non-productive team member, and if problems do crop up, the engagement lead can provide an answer right there without pausing to rope in a project manager.

In hindsight, it’s not surprising that our clients like having maker-leaders running the show. But we’ve also seen our makers-as-leaders policy pay off in terms of employee retention. Especially at a time when trust in executives is at a record low, our team members appreciate that their leaders understand what they’re going through. We’re all more likely to trust and communicate with people who we can relate to.

Would we ever hire a leader who can’t create? Probably not. In a room full of makers, people who can’t create are at a disadvantage. We do try to add diverse perspectives to our team, particularly individuals with sales skills, but there’s just something about people who build that non-makers can’t understand.

What We Look for in Maker-Leaders

Of course, not every maker is cut out to be a leader. To figure out who to promote, we look for five distinct characteristics:

1. Multitasking ability

Bandwidth. Juggling ability. Whatever you want to call it, our leaders must be able to jump back and forth quickly between projects. When you’re creating something totally new, you never know when fires will flare. We look for leaders who can help code one thing, map out an architecture for something else, rock a client review meeting, and then chat about still another project’s scope. We’ve found that makers tend to stay focused and on task better than others when things get that hectic.

2. Empathy

There’s no way around it: We work in a stressful business with stressed-out clients. Our leaders must be empathetic enough to understand what clients need, what challenges they’re facing internally, and how to assure them that we’re on their side. If a client feels like we don’t get it, we’ve already lost, no matter how good our work might be.

Empathy helps internally, too. Eighty percent of employees work harder for more empathetic employers. When we’re up against tight deadlines and projects turn into problems, leaders who know what our team members are going through are critical.

3. Decisiveness

Analysis paralysis is an affliction of inexperience, so we need people who’ve done the work. Because we pride ourselves on speed, we encourage our teams to make choices rather than wait for someone else to tell them what to do. That doesn’t mean we make rash decisions, but we believe fast decisions are better than nothing. At least a decision, good or bad, tells us something new.

Few leaders know more about the need for speed than Greyhound CEO Stephen Gorman. “A bad decision was better than a lack of direction,” Gorman recently told Harvard Business Review. “Most decisions can be undone, but you have to learn to move with the right amount of speed.” While we’re not working on deadlines quite as tight as bus schedules, our leaders must be able to internalize information and make snap judgments.

4. Energy

We fail every day — ideally multiple times. Failure is perhaps the most important ingredient in our experiment-driven design process, but it can also be incredibly stressful for people who aren’t used to it. When we’re struggling to find the right solution, all that failure can crush team morale. We rely on our leaders to keep teams motivated and flowing with positivity. Eureka moments don’t come to teams mired in misery.

5. Goal-setting skills

One of the reasons we can move so quickly is that we’re strong goal setters. Whether a client wants to cut project costs, add new features, or switch up a sprint, we depend on our leaders to set realistic but challenging deadlines for themselves and their teams. Our leaders break objectives into tasks for team members, who we give lots of autonomy, and then hold everyone accountable for accomplishing them on time.

While we put makers at the wheel whenever possible, we don’t force anyone into a role they don’t want. Plenty of developers and designers are content to continue honing their craft, and we respect that. But we recognize the talent, intellect, and downright grit within people who build new products. We want those people on our factory floor, managing others, and even steering our company. Don’t you?